Blade Edge, Thickness, and Beveling

.jpg)

Blade Thickness

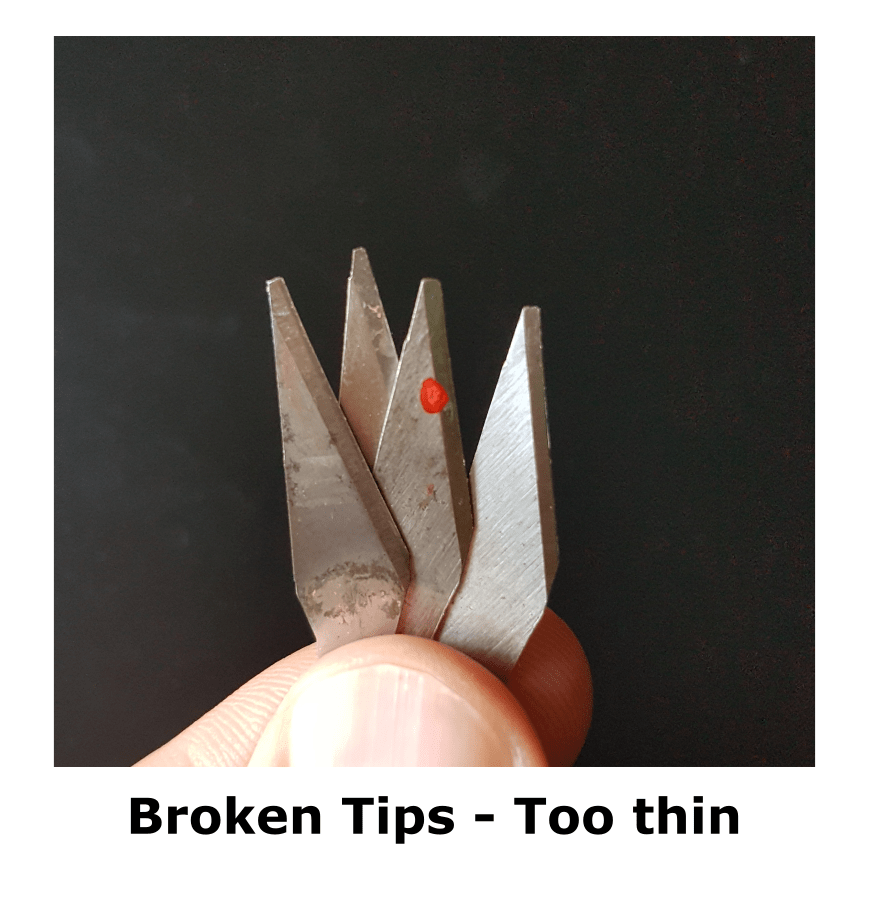

How thick a blade is will affect how strong it is, as well as how well the blade can cut. Thicker blades will be stronger. Thinner blades will have a slimmer profile - which allows for easier and better slicing. The choice of blade thickness comes down to compromising between strength and slicing ability. There is a reason we don’t all just carry around Exacto knives in our pockets. The blades are too thin. They break too often; and aren’t as reliable as a real pocket knife. The picture on the right there shows a few of Jake’s Exacto blades with broken tips.

.png)

We don’t carry around a metal rasp either. All a rasp can do is scrape, not cut. As a knife designer, I navigate the territory between the two extremes. However, the most important factor in designing a knife is the intended purpose of the blade. Sometimes the purpose is clear cut. Self-defense and combat knives need to be sturdy. They need to hold to the rigors of combat. Survival knives need to be able to take the abuses of hard use. A fillet knife needs to be able to slice with excellence and be thin enough so that the blade can flex as needed.

Everyday carry knives have their own considerations as well. Although there is not one specific task set for them, there may be a particular niche I want to fill. The blade may be overbuilt and solid like a Zero Tolerance blade. Or a businessman may want a light, thin office blade that can slice through paper like butter - like my Titanium Lockback (pictured below). As a designer, I have to look at what kind of tasks the user will want to accomplish.

Once I’ve decided on a thickness, I can choose a grind that will either help reinforce the attributes of that thickness, or try to make up for any weakness. For instance, if you have a thick and strong blade, I can choose to go with a flat or hollow grind to reduce the weaknesses of a thick blade. Even though the spine of the blade is thick, the profile of a flat or hollow grind will not offer as much drag to the blade as it slices through a material.

There is a difference between “slice” and “cut” in the knife world. For our purposes in this article, cutting means to separate into parts or to sever. Slicing means to move through with a sharp object. This distinction is important when it comes to the thickness of a blade.

Any knife, properly sharpened, with almost any design or blade profile can be nearly as sharp as another knife. There are a few things that might moderately affect it, but as long as the edge has the same thickness, it will cut about as well as another knife. So if I have a very thick blade, but it tapers down to a thin edge, it can be as sharp as any other blade.

.jpg)

If you are cutting something and you don't need the knife to go through the material, it doesn't matter how thick the spine is, it is down to the the edge grind, the workmanship, and materials at that point. However, if the blade has to pass through the material, for instance corrugated cardboard, or even an apple, then different designs in the blade will affect how much drag the blade has on the material. In this case, flat and hollow grinds will be superior to sabre grinds. Take a look at my Blade Grinds Article for more about grinds. In the picture on the right, the sabre ground Ka-Bar Companion (1/4" thick spine) goes through some cardboard well enough - but not quite as well as the much thinner, flat ground Titanium Lockback would. It is entirely possible that for cutting tasks the difference will not be enough for you to notice, but when it comes to slicing the overall thickness of the blade is much more important.

For a thin blade, I can choose to reinforce the blade with a sabre grind, so that the blade is a bit stronger than it would have been otherwise - due to the extra steel reaching farther down and reinforcing the blade. Or I can use a flat grind, such as the Titanium Lockback, to really reinforce the benefits of the thin blade. It now has exceptional cutting ability. On the other hand, it is not designed to have the strength or weight for chopping, prying, or heavy piercing. It is designed to slice, and to slice very well. But it is not meant to be used as a screw driver or a can opener.

It comes down, once again, to trade offs: Strength versus slicing ability.

Edge Thickness

The edge thickness has the same related tradeoff in strength versus cutting ability. Generally, the thinner edge will cut better, but is weaker. Thin edges risk rolling over or chipping. A thick edge is strong, but will not cut as well.

A quick note: The edge of a knife can get confusing with different terminology. There is not industry wide terminology for the grind of the edge of a knife. The edge grind and the blade grind often get confused in conversations by makers and knife enthusiasts alike. My knife engineer, Phil Gibbs, refers to it as the Canel (CAN-ELL). But for simplicity’s sake, I will refer to it as the Edge Bevel to avoid confusion.

The thickness of the Edge Bevel is determined by the designer. A big, hunky chunky knife can be extremely sharp with a thin edge. A thin stock knife can have a relatively thick edge with a wide angle. There is no right or wrong answer per se, it is simply a matter of what you want to accomplish.

The image below compares my Serpentine Stockman (bottom) to the Ka-Bar Becker Companion (top).

.jpg)

The pocket knife shows a flat ground, Sheepsfoot blade. I chose my preferred 30 degree (15 edge side) blade edge for this knife. This accentuates its slicing ability, and allows for an extremely sharp blade. The Ka-Bar Companion is a big, hunky chunky blade. The spine is ¼” thick steel, and it features a sabre grind rather than a flat grind. The sabre grind reinforces the benefits of a thick knife stock. The blade is tough, and extremely unlikely to break. The Edge Bevel is also ground thicker than the sheepsfoot. So the Companion is not as sharp as the sheepsfoot. But the Companion isn’t designed to be a slicer. It can pry, chop, and pierce things that the sheepsfoot cannot.

The Companion could be sharpened to the same angle and sharpness of the sheepsfoot. Then it would be as sharp as the sheepsfoot. But it would have a lot more drag, as the knife is a lot thicker and has a sabre grind. It would cut well, but it wouldn’t slice into material as well. I like that the designer went with the strengths of the knife, rather than try to make up for the “weaknesses.” If a user really wanted to, changing the edge bevel thickness would be as simple as sharpening it to a more acute angle - though I typically do not suggest changing a knife's design. Typically, a lot more thought goes into a knife design from the designer, than the knife excited knife used with a grinder. It can be loads of fun to adjust a knife to your own preferences, but take some time and think it through, and maybe even do a little research. Many times a particular steel was chosen for specific properties, and the blade was designed around that steel, or perhaps more accurately the steel was chosen for the design.

The thickness of the blade’s edge is one of the few things that can be easily changed by the knife owner (rather than simply being predetermined by the maker). If you want your knife to cut smoother and easier, you can sharpen the edge and thin it out. I personally prefer my edges to be at a total of 30 degrees. Some makers disagree with me, and prefer a thicker edge of 40 degrees. There are a few who go even thinner than I do. If you go thinner than 30 degrees, and your blade is chipping or rolling out too much, that will indicate that you need to thicken your edge. A little more sharpening at a wider angle and it will strengthen as the blade thickens. Don’t eat too much of your blade away though, or you won’t have much left! If you are interested in learning more about sharpening, take a look at my Sharpening Instructional Videos. Or if you prefer reading, my sharpening on a stone article will take you slowly step by step through the process.

The Primary Bevel and Secondary Bevels

Many knives have two bevels. If you look at, say, a Randall, you will first see a bevel that starts from the middle of the knife and goes most of the way towards the edge.

This is the primary bevel. Even if the blade is flat ground, the steel still slopes downward towards the edge in the Primary Bevel. At the very edge, there is a secondary. Edge Bevel. Most knives have this kind of geometry where a shallower Primary Bevel meets a little bit wider Edge Bevel. This leaves the edge just a bit thicker for strength and durability. The Swedge at the top of the blade reduces the thickness of the blade at the tip, and allows for easier piercing.

Some knives do not bother with the Edge Bevel at all. Scandanavian knives like the Finnish Puuko only have a single bevel that goes all the way down to the edge. Technincally the puukko is a sabre grind, but it only has the one primary bevel that goes all the way. Because of this the edge ends up being a thin, high performance edge rather than being a strong edge. The steel stock (the widest thickness on the blade) on a puukko is normally thin, add in that the shallow Primary Bevel is the only bevel, and you have a knife that can cut really well. The Swedish Mora knife is also very similar in design to the Finnish Puukko.

Certain chisel ground knives also use the Primary Bevel for the edge. Again, this usually means the edge has a thin angle and allows for a very sharp edge. Of course there are many chisel ground knives that also incorporate a secondary Edge Bevel.

Another example of a single Primary bevel acting as the edge bevel is the convex grind. The convex grind rounds into the edge. Axes commonly use the convex grind. The image above shows the Gransfors Mini Hatchet which uses the convex grind. The Esee Knife company also uses the convex grind extensively, and has built up a loyal fan base. The convex grind, done properly, does strengthen the edge of the knife. They can be difficult to sharpen if you do not have experience and or access to several grades of slack sandpaper belt however.

In conclusion, the edge, blade stock thickness, and beveling presents similar trade offs for the designer as the other design decisions. He must decide if he wants strength or cutting ability - and must find a balance between the two. While the blade's performance can be affected by blade shape and profile, often it comes down to the angles of the Edge Bevel. The next article in this series is the Blade Grind, check it out and learn more about the different types of grinds.

Thank you for reading. I hope you now understand more about how blade and edge thickness can affect performance. Stay tuned for my next article in my Knife Characteristics series.